How an empty grave symbolises the Battle of Jutland's large loss of life

In a quiet corner of the Templecorran cemetery in Ballycarry, the McMaw family gravestone mentions Richard, a young sailor lost during the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

Richard was from Eden village near Carrickfergus and was a stoker on HMS Queen Mary. He is not buried in Ballycarry: only one casualty of the 1,246 men on the Queen Mary who were lost actually has a grave – a seaman named Humphrey M. L. Durrant, who was rescued, but later died and was buried in Dalmeny, Queensferry, in Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwenty survivors were picked up after the Queen Mary sank, most by the Royal Navy. The bodies of the rest of the crew who perished were never recovered from the waves.

That stark statistic gives some sense of the losses sustained during the largest naval engagement of the First World War.

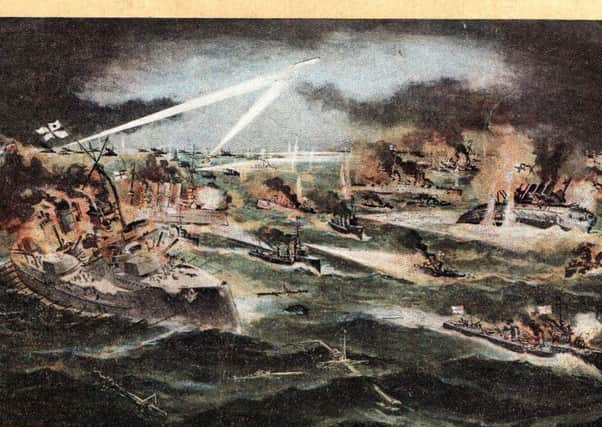

The Battle of Jutland was fought on May 31 and June 1, 1916 in the North Sea. It was fought between the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet and the Imperial German Navy’s High Seas Fleet. The German aim was to destroy part of the British fleet and break the naval blockade of Germany at that time. In total, 250 ships were involved in the battle and 14 British and 11 German ships were sunk. Six thousand British sailors perished in the brief, but fierce conflict, and around 2,500 German sailors.

When the war had broken out, the German High Seas Fleet was outnumbered and outgunned. The Royal Navy had more modern battleships and battlecruisers, and it was felt that any major sea battle would lead to defeat for Germany. German warships made forays into the North Sea, bombarding coastal towns such as Great Yarmouth and Hartlepool, hoping to lure out British warships which could be attacked by submarines, or led towards a stronger German force waiting over the horizon, thus reducing their opponents through attrition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter several engagements over the course of 1915 and early 1916, a full-scale battle became increasingly likely. Sailors on both sides were waiting for ‘Der Tag’, the day when the world’s strongest fleets would finally clash. That clash came off the Danish coast, at Jutland, on May 31.

The Royal Navy lost more ships and twice as many sailors as the Germans. But the Germans failed in their objective and they never again contested control of the high seas with their battleships, preferring unrestricted submarine warfare. Both sides claimed victory from the Battle of Jutland.

The ferocity of the battle was recounted at the time by Surgeon Practitioner Robert Paul, who had been a student at Queen’s University in Belfast when the war had broken out.

“The sea was boiling with shells on every side of the Invincible and the spray was blinding. The sky was in some patches black with smoke and mist; in other places it was aglow with burning ships” he wrote to his father in Limerick.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong those who were to die in the harsh waters of the North Sea were many men from Ulster. The Weekly Telegraph newspaper of June 10, 1916, informed readers: “Great anxiety prevails in Belfast as to the losses sustained among warrant officers and men of various ratings of the fleet in the North Sea battle.”

The details of locals who had perished soon began to appear in the newspapers at home. Among them were two brothers, John and Robert Crothers of Belfast. John was on the HMS Defence and when the war broke out he came back from the United States to enlist, having previously served in the Royal Navy. He was married and worked on the Head Line Company. Robert had also previously been in the navy and had re-enlisted. He had been in Australia when the war broke out.

Larne men Robert Gribben and William Moore, both of whom had been members of the Naval Reserve called up as a result of the war, had also been lost on HMS Queen Mary.

Gribben was a coal filler for two local firms at the Bank Quays outside the town, and left a wife and five children to mourn him. So too did William Moore, a stoker on the ship. A death notice was later posted in the local newspaper for Moore from a local Black Preceptory, Joseph’s Chosen Few RBP 47.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were men from across the province who had lost their lives, including Stoker Bernard Chambers from Carrickfergus, Engine Room Artificer Robert Kerr from Newtownstewart in Tyrone, and Stoker John Forrest of Tullyhogue near Cookstown. Surgeon J. S. D. MacCormac was lost on the HMS Black Prince and was from Banbridge, while Able Seaman James Morrow was from Killyleagh, also in Co Down.

Seaman George Smiley of HMS Black Prince was a member of St. Matthew’s Church in Belfast. At least four Belfast men went down with HMS Indefatigable; John Woods, Douglas Sloan, Henry Jelly and James P. Reilly, while Stoker George Gallagher was also lost and was a son of George Gallagher of Rosemount in Londonderry.

Other names were detailed in the newspaper reports in the aftermath of the battle: Petty Officer John Dawson Cochrane of Wolff Street, Belfast; First Class Stoker William Forsythe of Woodvale Road; Able Seaman Joseph Pollock of Epworth Street, Belfast; Gunner Thomas McCann of New Lodge Road; and Able Seaman George Smylie of Lanark Street.

Newspaper headlines highlighted the Battle as the “Greatest of Sea Fights. The North Sea Victory. Enemy’s terrible losses. Thrilling battle scenes”, but the reality of the losses behind the jingoistic headlines were striking home to many local families.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe young age of many of those who perished is also clear from newspaper accounts. Private T. L. Crossan of the Royal Marines, was just 20 years of age when he was lost on HMS Defence. His brother and sisters lived at Mossley. Another local man on the same ship was Able Seaman Hugh McAuley, who was 29 years old and from Benares Street in Belfast.

The outcome of the Battle of Jutland had a long term consequence in that the Germans began to rely on a campaign of submarine warfare in February, 1917. Two months later, partly in response, the USA declared war on Germany and entered the conflict on the side of Britain and her allies.

More than 100,000 men had fought at Jutland. Over a few brutal hours, some 8,500 lost their lives. The greatest tragedy for families such as the McMaws of Eden near Carrickfergus was that their son Richard – like so many others – would have no known grave.

- Dr David Hume, MBE is a writer, historian and commentator on cultural and historical matters and is author of several historical publications on local history, Ulster Scots, and Irish history.